What is the Relative Wage Coordination Argument?

The relative wage coordination argument points out that even if most workers were hypothetically willing to see a decline in their own wages in bad economic times as long as everyone else also experiences such a decline, there is no obvious way for a decentralized economy to implement such a plan. Instead, workers confronted with the possibility of a wage cut will worry that other workers will not have such a wage cut, and so a wage cut means being worse off both in absolute terms and relative to others. As a result, workers fight hard against wage cuts.

These theories of why wages tend not to move downward differ in their logic and their implications, and figuring out the strengths and weaknesses of each theory is an ongoing subject of research and controversy among economists. All tend to imply that wages will decline only very slowly, if at all, even when the economy or a business is having tough times. When wages are inflexible and unlikely to fall, then either short-run or long-run unemployment can result.

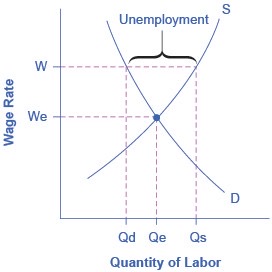

Because the wage rate is stuck at W, above the equilibrium, the number of those who want jobs (Qs) is greater than the number of job openings (Qd). The result is unemployment, shown by the bracket in the figure.

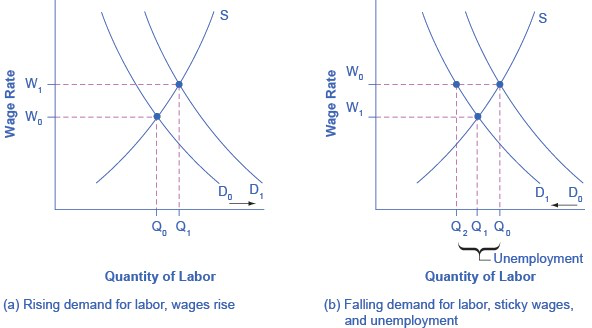

The above figure shows the interaction between shifts in labor demand and wages that are sticky downward. This figure demonstrates the situation in which the demand for labor shifts to the right from D0 to D1. In this case, the equilibrium wage rises from W0 to W1 and the equilibrium quantity of labor hired increases from Q0 to Q1. It does not hurt employee morale at all for wages to rise.

This figure shows the situation in which the demand for labor shifts to the left, from D0 to D1, as it would tend to do in a recession. Because wages are sticky downward, they do not adjust toward what would have been the new equilibrium wage (W1), at least not in the short run. Instead, after the shift in the labor demand curve, the same quantity of workers is willing to work at that wage as before; however, the quantity of workers demanded at that wage has declined from the original equilibrium (Q0) to Q2. The gap between the original equilibrium quantity (Q0) and the new quantity demanded of labor (Q2) represents workers who would be willing to work at the going wage but cannot find jobs. The gap represents the economic meaning of unemployment.

In a labor market where wages are able to rise, an increase in the demand for labor from D0 to D1 leads to an increase in equilibrium quantity of labor hired from Q0 to Q1 and a rise in the equilibrium wage from W0 to W1. (b) In a labor market where wages do not decline, a fall in the demand for labor from D0 to D1 leads to a decline in the quantity of labor demanded at the original wage (W0) from Q0 to Q2. These workers will want to work at the prevailing wage (W0), but will not be able to find jobs.

This analysis helps to explain the connection that we noted earlier: that unemployment tends to rise in recessions and to decline during expansions. The overall state of the economy shifts the labor demand curve and, combined with wages that are sticky downwards, unemployment changes. The rise in unemployment that occurs because of a recession is cyclical unemployment.